Friday, December 31, 2021

Walking Alleys in the Time of Covid-19—Bizarre? Or Normal?

Sunday, October 24, 2021

Images of a Coastal Trip Stored for Winter Browsing

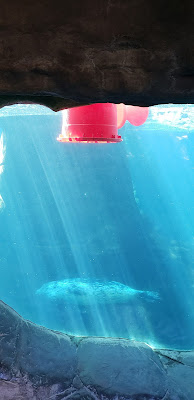

When there is snow on the ground this winter and its dark in the canyon by 5 o'clock, sometimes I'll picture the coast as I saw it in late summer. I'll remember the the smooth glide of the seals under their brillantly-colored toys in the tank at the Newport Aquarium or the silly-looking seaside telescope surveying Nelscott Beach.

I'll remember the feel of the cool sand on my bare feet on the evening walk on Nelscott Beach or the hip pain of trudging through the thick white sand on the Oregon Dunes—each step sinking deep while the dune grass shadows beckoned us onward encouragingly.

At Agate Beach I had to stand on my tiptoes to catch a glimpse of Yaquina Lighthouse over the sand dunes that were level with my head as I walked down to the water. The lighthouse appeared like a white pencil tip stuck on the hills over the top of a dune. Can you find it?

A lighthouse is a beacon for tourists like me. During an earlier winter, the memory of the red and white lenses at the Umpqua Lighthouse warmed my thoughts. This summer I got to climb up into the lighthouse's cap of lenses and was bathed in a pinkish light. It was glorious!

Who isn't moved by the perpendicular lines of a lighthouse?

My sister and I visited the old Coast Guard Station house next to the Umpqua Lighthouse. We wandered it's rooms, and read tales of heroism. What vision will stay in my mind from visiting it, might you ask? I think it will be the light and brush of leaves against a window—in the women's bathroom. Not a particularly historic spot, but stunning nevertheless.

During this winter's gloom-filled evenings, I'll also recall the colors of sea-nurtured life in a tidepool below Yaquina Lighthouse.

And I'll remember the brillance of jellyfish—those washed ashore on beaches and those blue ones, perpetually floating in the water of a tank at the nearby Newport Aquarium. The jellyfish tossed on the sand by incoming waves can't survive outside the water. They act as prisms until their water-filled bodies drain and their skins' dissolve or are reclaimed by the sea.

If those images are not enough, there is always sunset at Haystack Rock at Cannon Beach.

Wednesday, October 13, 2021

Can I Convince You to Vacation in the Midwest?

Look under a mushroom and you might find Iowa.

(Isn’t it sad that white men decimated the herds of bison—sustenance for the Native population—and in exchange gifted them alcoholism and ironically bison on neon bar signs?)

I crossed North Dakota stopping only at rest stops and convenience stores, partly due to the state's high Covid-19 rates. I spoke with a nurse offering free Covid shots at a highway rest stop. She had given four shots in four hours. She shrugged behind her mask. Other than the National Park rangers at the Theodore Roosevelt National Park, she and one other woman were the only ones I saw wearing masks all day. My tally seemed to be an informal statistic that confirmed why North Dakota had a high rate of epidemic-related hospitalizations and deaths this summer. And why I kept moving. Maybe by the time you might visit, things will have changed. I would have loved to go slower and admire the county.

My favorite billboard on the entire trip was in Fargo, North Dakota. It was a chiropractor’s advertisement with a smiling gray-haired cowboy, who leaned forward on his horse and made eye contact as I drove by. It made me wish I had a horse. The ad read “Let Us Put You Back in the Saddle.”

The billboards throughout my travels portrayed a big part of Midwestern culture: an aging farm population and an enduring Christian presence. The well-meaning Pro-life billboards started showing up in North Dakota and continued being in evidence on highways the entire journey. Unfortunately, the only babies shown on every billboard—six Midwest state’s worth—were white babies. The signs contradicted the recent protests that systematic racism doesn’t exist in America. The impression was reinforced when one billboard had a blue lives matter flag on one half and on the other half a photo of another fetus worth saving—a white one again. I had expected to cross evidence of racism in the Midwest and it was one of the reasons that visiting there made me anticipate feeling uncomfortable. I just hadn't expected it to be so blatant.

As I drove into eastern Minnesota, hardwoods began appearing. Common hackberry, oak, elm, and maples circled farmhouses and silos or edged small lakes. I was delighted as the beautiful woods grew thicker. I spent a night on one of the lakes with new friends, Anita and John, who had an old cabin with a Finnish wood-fired sauna nestled against the lake’s bank. My hosts were lovely and their dog laidback and welcoming. When I arrived late afternoon the smell of freshly made grape jelly lingered. As an introduction to Minnesota, I was charmed. We even canoed a short distance in the morning before the dog jumped in the water and began following us, threatening to tip us over. We switched to the sauna.

Mid-morning I headed to the Twin-Cities area, where I loved the backyard concert in St. Paul and the Swedish meatballs and mashed potatoes served at the Swedish Institute in Minneapolis. I was glad to go by (even in a heavy downpour) and see the heartfelt tribute to an ordinary man who had died before his time.

|

| George Floyd |

Thursday, August 19, 2021

On the Edge of Awe

The flowers were astonishing this year. The lilies alone were lovely at every stage of their blooming.

The white globe before its opening, the dancing of the full petals in the breezes, and the lilies’ fading stage, a lovely, muted pink. Humanity’s many colors, like those of flowers should be a source of delight. Would that the world would appreciate skin tones like the colors of petals. Nowhere on the park trails did I hear anyone deriding the pink of the heather or the purple of the asters. Everyone commented on their beauty.

Friday, July 16, 2021

Awe

Warding off dread, I am coating my cabin and outbuildings with a fire retardant. An effort that gives me only a slight feeling of assurance. Avoiding the sun, I work on whichever side is in the shade. Sometimes I take a break by hiking further up the canyon along a stream or join a friend at the river's edge as he fishes in the river.

My friend reminds me not to let my shadow fall on the water and scare the fish into their own version of shock and awe. What do fish make of their own shadows? My friend and I came across a dozen small trout swimming in a sunlit pool in a mountain stream. There appeared to be twice the number of fish until I realized I was also counting their shadows. The beauty of the pool, the movement of the fish and their shadows, and the delight in finding trout gave me a brush with awe, the reverant kind.

Can you find the fish?In Microadventures: Local Discoveries for Great Escapes, the author Alastair Humphreys suggests, “I can guarantee that within a mile of where you live, there will be something that you’ve never seen or noticed before.” Studies show these small moments of surprise, of awe, contribute to good health. I have many of these moments in the canyon.

This spring I found a Pacific Tree Frog, caught him, and then let him go in the boggy area across from my cabin. I have been wishing for the evening sound of croaking frogs. Maybe this little guy will start the tradition.

Further up the canyon it is the water that holds the awe. Maybe it is the scarcity of water this summer—I can’t hear the river from my cabin this summer—that makes me appreciate any trail with deep enough water that its rivulets still make music. Listen.

This summer, if I am to have "Microadventures" of the less dreaded type, I have to ignore the dry tips of pine needles, the yellowed sunburnt leaves, and the lid in the road proclaiming water where none is evident.

Instead, find pleasure in the leap of a single drop of water.

Or an eight-inch high waterfall slipping over red volcanic rock and making a froth of bubbles, each one tinged blue and green reflecting the sky and the trees. A lovely sight.

May your summer be filled with awe of the less dreaded kind.